Contemplation

With Inga bruised and battered in Newport, I had a decision to make—to push on or to step off. It was a decision unlike any I had faced before.

Broken/missing planks on Inga’s bowsprit

Sheared off nav light

To appease my parents, I hastily agreed I was finished. However, my lingering indecision was obvious enough. Proof of which arrived as a letter. Believing I would be too stubborn to remain ashore, my mom broke into tears at work.

Though we had never met, a long-time colleague to my mother wished to share her brother’s story.

He was a competitive high school swimmer, an expert diver, a generational fisherman, and a husband to a pregnant wife. All that ceased to be somewhere between Cape May and Atlantic City. While crewing a clam dredge, his boat went down. The sea kept his body. No “perfect storm.” No nor’easter. All to blame were the ever-present, massive dangers of a cold North Atlantic.

I held my breath as I read each soul-piecing word.

Inga was headed there next.

My mind wrestled with the impossible calculus of abstract questions, possibilities, and probabilities.

Could our problems be resolved? Was walking away quitting? Was continuing stupid and reckless? Had I been grossly naïve or foolish for leaving my job? What were the best and worst possible outcomes? How likely was one versus the other?

Had I failed or succeeded? Was this an end or a beginning?

The futility of certainty in answering such questions was obvious. Yet, I was little deterred in my initially desperate struggle to obtain nothing less.

Part of me couldn’t resist selfishly hoping Guillermo might spare me by electing to spend the winter in New England. Similarly, I sought guidance while secretly longing to be told what to do.

However, I also consciously appreciated how deflection would only undermine my original intentions. Beyond sailing to distant shores, my primary motivation had been to use this experience to make peace with and practice navigating through uncertainty. Testing my character and decision-making abilities were what I hoped would make pursuing the opportunity worthwhile.

So, leaning into the unrelenting ambiguity, I began my contemplation.

…

Volatile thoughts filled long hours spent driving between Newport and Portland or down to my sister’s college graduation in Harrisonburg, VA. My perspective oscillated between extremes—frustration and gratitude, fear and hope, reason and faith, defeat and inspiration.

Contemplative scene from Morse Mountain Seawall

For example, I have repeatedly been told to gauge success by whether you get your desired outcome.

If my desired outcome was a place. Florida. Patagonia. The South Pacific.

Then yes, I failed.

But success has rightfully been defined in other terms. Take Churchill’s “going from failure to failure without loss of enthusiasm” or Bob Nardelli’s “how much you accomplish against stretching yourself.”

During those deceptively long fifty-six hours at sea and in the weeks leading up to them, I learned such an incredible amount. I pushed myself to the brink. Sure, some lessons might sound elementally simple on paper, but forged in adversity they possess beautiful and transformative depth.

What had I gained?

For starters, a reality check.

That’s something we all may need now and again. A stimulus to reorient our perspective and our priorities. Something to set us back on track.

In the crucible of the moment, I was also offered an unfiltered glimpse at my true character.

It wasn’t all pretty.

Like anyone, I have dreamed of how I might measure up to some test of willpower or moral strength, perhaps placing myself in the shoes of some novel, film, or real-life protagonist. However, my suffering onboard exposed glaring chinks in my armor. I felt compromised by weaknesses I would have previously denied. Vomiting for the twentieth time, unable to think, covered in bodily fluids, amidst growing dissension, dehydrated, freezing cold, hungry, isolated, and surrounded by unrelenting wind and seas, I faced the possibility that I had a breaking point.

However, in that imperfection, I also found real knowledge of how I respond to fear. Above all, I realized my potential to be truly courageous.

I was reminded that what we aspire to be will always be unfathomably more difficult or demanding than we anticipate. Also, that the way forward is won a single small battle at a time.

Both my discipline and affection for preparation had been powerfully revitalized.

There was a right way to go about such a goal—to be relentless, methodical, patient, and accountable. There was a wrong way to go about such a goal—to be cavalier, hasty, uncritical, and overly reliant. Circumstance and ignorance were poor excuses. I had erred towards the latter. However, the experience didn’t stop at revealing what I needed to do better, it showed me how. Sailing or not.

“It’s about being a warrior. It doesn’t matter about the cause necessarily. This is your path and you will pursue it with excellence. You face your fear because your goal demands it. That is the goddamn warrior spirit. Give yourself 100% focus because your life depends on it.” — Alex Honnold

How could such insight and motivation be deemed a total failure?

By some accounts maybe it had already been a glowing success.

Plus, there was more.

Guillermo offered me a glimpse at a grace under pressure which Hemmingway would applaud.

My admittedly callow view of “fate” was structurally reformed. Somehow, I had misinterpreted Paulo Coelho’s message.

“when you want something, all the universe conspires in helping you to achieve it” — The Alchemist

In The Alchemist, Santiago dreams of a treasure among the Pyramids. He traverses a sea and a desert experiencing both setbacks and miracles. Upon reaching the end of the line, and when all hope seems lost, he learns his treasure was where he began all along.

The universe may conspire, but it does so in unpredictable ways.

The treasure isn’t always obvious. It’s never something to be found in one place. It often doesn’t appear as expected.

Someone told me, “Don’t be so concerned with the sense of an ending.”

Success. Failure. Beginning. End. Grit. Quit.

These questions were a distraction—absolutes never meant to be weighed against a static past. They were and would remain prospects defined by present and future action, by whether or not I continued my commitment to self-improvement.

I was where I was. There was no changing the past.

I would never know all the facts. Nobody could control all the risks. There was no crystal ball.

In a real world, bound by uncertainty, the perfect decision would be a function of my best effort. It was doing all I could with what I had. It was using what I had learned. It was balancing emotion with reason. It was having faith, but also patience.

Regardless the outcome, that would produce a decision worth believing in.

“Trust in the Lord with all your heart and lean not on your own understanding” — Proverbs 3:5

“The magic of doing your best” — CVANLO

So, I got to work.

…

Hours, if not days, were spent absorbed in research. Articles, forums, papers, and books crowded my browser windows and office.

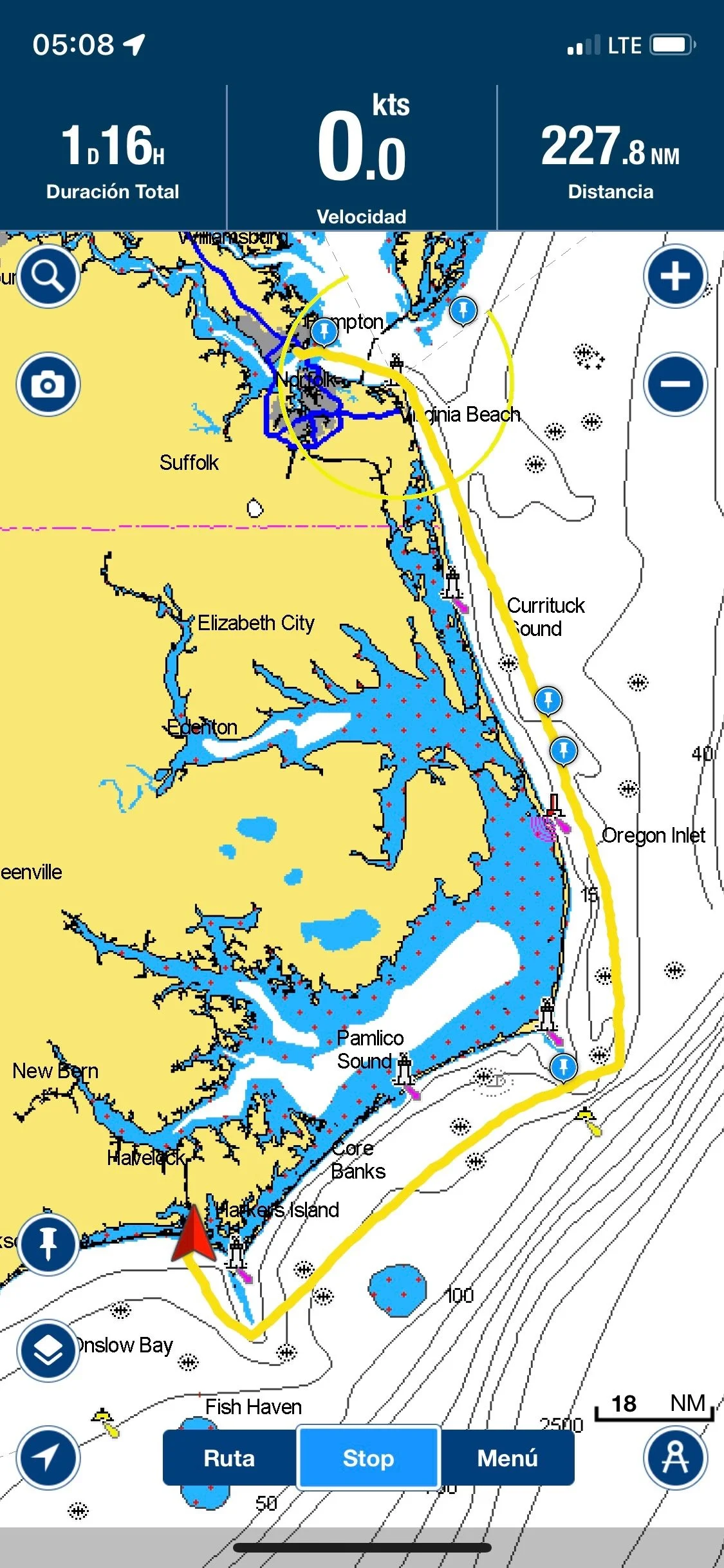

I poured over marine charts, plotting out potential waypoints one by one.

NOAA 12300 (NY Approaches – Nantucket Shoals To Five Fathom Bank)

NOAA 12200 (Cape May to Cape Hatteras)

NOAA 13003 (Cape Sable To Cape Hatteras)

NOAA 13205 (Block Island Sound And Approaches)

NOAA 11520 (Cape Hatteras To Charleston)

NOAA 11009 (Cape Hatteras To Straits Of Florida).

If the letter I received gave me a reason to think twice, Cape Hatteras kept me up at night. That is no exaggeration.

Multiple nights I awoke from vivid dreams in which Inga was slammed or knocked down by ferocious storms along Cape Hatteras’ infamous shoal coast.

Adding to my nervousness, a thirty-foot sailboat went missing on a trip southbound along North Carolina. The boat and crew were eventually found adrift well out to sea after a weeklong search. They were lucky to be alive. The boat had been de-masted, every critical system was destroyed, and the crew had depleted their fresh water.

Long Island Sound and Jersey Shore may have strong currents and lots of traffic, but Hatteras is the “Graveyard of the Atlantic.” There thousands of ships have met tragic fates. Think about that. Thousands.

Extending from the Caribbean to Northern Europe, the Gulf Stream runs generally about sixty miles wide and four-thousand feet deep. In total it carries a quantity of water greater than that of all Earth’s rivers combined at an average pace of roughly four knots (mph). If that doesn’t sound significant… it is.

Off Hatteras, it flows at a phenomenal eighty million cubic meters per second. The stream of warm water produces fickle and unpredictable surface weather.

Hug the shore and you trade northbound current for treacherously elusive shoals. Marine charts contain a disclaimer admitting that Diamond Shoals extending past the cape is effectively uncharted due to constantly shifting topography.

Coastally, compasses typically observe three to six degrees of additional magnetic variation.

There are no feasible inlets or anchorages for nearly two hundred miles once you depart from Virginia.

Prevailing winds come from the NW this time of year. Usually, low pressure systems pass through every three to five days. Favorable conditions occur when the second half of a high moves West to East, over the coast and then offshore. Winds will shift from NW to NE before dying down or shifting to the S/SE.

If you mistime the system and enter the Gulf Stream too soon even moderate winds out of the North will cause you to be ravaged by massive and confused seas.

Altogether, these variables make a potent recipe for disaster.

Outside of waiting for a better time of year, heading South you have three options. Unfortunately, none of which involve changing the weather.

There is the coastal run with the dangers that I’ve outlined.

Alternatively, you can head offshore, passing through the Gulf Stream. This route is extremely inefficient unless planning to bypass Florida and head straight for the Caribbean. It also necessitates great confidence in both your boat and crew. Sailing hundreds of miles offshore for nearly a week, you are almost guaranteed one bout of sketchy weather.

Lastly, you have the Intracoastal Waterway (ICW), which runs all the way down to Florida. Some of the deepest and widest sections of the ICW happen to be through the Carolinas, allowing most sailboats to dodge Hatteras. However, it is not advised for boats with keels drawing greater than seven feet below the waterline. Max mast height is restricted to a firm sixty-four-feet. Inga barely, barely, makes the cut. Not to mention this would be Guillermo’s absolute last choice.

…

As notes filled pages of my sailing journal, my prior ignorance seemed to grow exponentially before my eyes.

How could I have allowed myself to be so drastically uninitiated and underprepared?

It appeared I had conflated effort and involvement preceding our departure with accurate and sufficient understanding of what I was getting myself into.

We are all wiser in hindsight, but I was disappointed with myself. At least, I remained grateful for the chance to realize as much from the relative safety of dry land.

Not to mention, part of the problem remained. I didn’t know what I didn’t know.

Sure, Guillermo and I improved our communication and refined our expectations.

Between visiting sailmakers and hardware stores, we sat for a couple long and rainy coffee chats in Newport. In doing so, we agreed upon necessary changes to our sail plan, reefing strategy, and routing. We discussed backup options along our future course.

Forums and articles offered loads of insight which I forwarded readily.

Yet, I remembered Peter, who offered us the most prescient advice before leaving Yarmouth. I knew nothing could replace speaking with an experienced individual. That was my best hope of filling the gap of unknown unknowns.

Furthermore, I was growing weary that reading alone was renewing my false confidence. I sensed I was wrongly treating the ocean like the admiral of an enemy ship, merely a matter to be tactically outmaneuvered.

That was the mindset which had humbled me in the first place. Analytical but over simplistic, resorting to an inflated emphasis on theory and emotion was not the right answer.

Now I understood it was a lot easier in theory than in practice.

“In theory there is no difference between theory and practice, in practice there is” – Yogi Berra

I wanted to hear from someone who had done it.

…

Two candidates emerged, one owned an Alberg-35 and the other a Peterson-44. Each had tremendous experience cruising or delivering boats along the East Coast.

Over the course of two generously lengthy conversations, a clear consensus emerged. The trip remained possible, doubtlessly so if Inga utilized the ICW.

BUT would it be worth it?

Paul Dunn, owner of the Alberg-35, told me he always used the ICW rather than rounding Hatteras. He was a cruiser with no budget for time. Safety was his priority.

To him, continuing didn’t sound fun.

Russel Fraser, owner of the Peterson-44, said the coastal route was in play at a price. Weather windows would be few and far between. Moseying down the coast might take months. One to three days of sailing between unknown weeks of waiting.

That’s not to say the inherent risks weren’t still relevant. Pushing a weather window or mistiming a nor’easter could have devastating consequences. They complemented their opinions with tide and wind considerations along the Jersey Shore, specs for the ICW, and recommendations for weather routing services (Chris Parker) and ideal ports.

Paul Dunn added that “just because everyone is leaving the harbor doesn’t mean you have to.”

He meant to do what felt right rather than what seemed right.

Above all, it became clear the best-case involved more motoring than sailing. If the goal was logging sea miles, sailing, and seeing new places, there were better alternatives.

…

On Christmas day, I began and finished The Proving Ground by G. Bruce Knecht. Similar, albeit less eloquent, to Sebastian Junger’s, The Perfect Storm, it’s about the 1998 Sydney to Hobart Race. That year, seven boats were abandoned (five of which sank), fifty-five competitors required rescue, less than half of the over one-hundred boats to begin the race finished, and six men died.

Billionaire Larry Ellison competed in the race aboard his seventy-four-foot super-maxi sailing yacht Sayonara. Limitless wealth and the most elite paid crew money could buy did little to insulate him from the surrounding danger and death. In the decades since he has faithfully upheld a vow to never again partake in open-ocean racing.

At face value, comparing conditions we had encountered with those of the infamous race sounds preposterous. As the book outlines, wind produces force exponentially. Increasing the wind speed from 50 to 60 knots equals a 20% increase in speed but yields a 40% jump in power.

Some boats survived where others did not. Luck played an elusive role, but I’m not convinced it was the deciding factor. As I read, the challenges, sensations, and mistakes from my experience played in parallel with those rendered in print.

Indecision. Disagreement. Fractured communication. A mishandled helm. Too much sail. Insufficient inspection. Shorted electronics. Faulty EPIRBS. Broken watch shifts. Insufficient emergency drill practice.

Inga became Sword of Orion. Blane was Glynn Charles. Guillermo was owner Rob Kothe. I was Adam “Brownie” Brown or Darren “Dags” Senogles.

Without explaining each real-life character, just know the semblance sent chills down my spine.

Importantly, as in the book, not all our shortcomings had been as simple as missed checklist items.

Sure, a couple of our most flagrant offenses were easily avoidable.

We found a trash bag’s worth of rubbish in the bilge while cleaning Inga in Newport. Remembering water creep higher and higher against a straining bilge pump will make me nauseous for the rest of my life.

Still, most faults were revealed by the sea, exposed like invisible ink when presented with a flame.

While on the phone with Russel Fraser, I mentioned Guillermo’s family would arrive soon.

His immediate response?

Seasickness was likely and we needed to plan shifts accordingly.

I had just learned something about that!

I wondered, was it telling that Guillermo and I never once considered it?

…

Guillermo’s family arrived on December 17th, just in time to watch Argentina win the World Cup and to catch a three-day forecast for light winds.

Inga was equipped with a new EPIRB, life raft, and propane heater. The torn mainsail was mended. Portlights were properly sealed. The missing nav light and fried electronics were replaced. With fresh provisions and clean tanks, she was ready to go.

Except, I was not on board.

I made my decision.

I received updates as they motored past Block Island, headed towards Cape May.

They made it there safely, though not under sail.

A few days later a second window appeared. They motored to Hampton, VA.

Yesterday, I got word they arrived in Beaufort, NC, successfully rounding in Hatteras under the blessing of light winds. They were chased by dolphins and Guillermo even caught a fish.

The news is bitter-sweet.

I am incredibly glad for Guillermo. A juggernaut of charisma. Though not without faults, he is a man who earns his good fortune.

He kickstarted my own journey. A journey I know is not finished.

My dreams were not lost at sea.

I believe my decision was the right one. It was the best one I could make.

But my heart still aches as they sail, or motor, away.

…

They say the best boat is the one you have.

I quit my job at the start of a likely recession. I risked my life with a couple of strangers.

I lived up to those Jim Croce lyrics:

“If it gets me nowhere, I’ll go there proud”

♪♪♪

“Like the fool I am and I’ll always be”

I figure I might as well try to get in a little more sailing. After all, I owe my conviction to acceptance—that there exists a better way to realize my vision.

A few more long months of winter remain before the tarps come off Papersails.

What’s next?

I’m as unsure as ever.

I do know Maine has 3,478 miles of coastline, more than all of California. Maybe that might be a good place to start.

More to come.