A Rude Awakening

I should have been more afraid.

…

At 8:33am on the 22nd of November, we began down the Royal River. This time we flawlessly weaved through the narrow channel and into Casco Bay.

Aware of my local expertise, Guillermo instructed me to pilot us towards DiMillo’s Marina. A final pitstop for diesel was all that stood between us and open ocean. Unfortunately, it was also as far as we would make it before things started to go wrong.

Within seconds of squeezing the diesel pump’s trigger, a pink geyser erupted back onto me. Diesel soaked my new jacket, my gloves, and even managed to nick the corner of my eye. I wasn’t sure how concerned to be about the lingering smell and mild sting which persisted after thoroughly flushing my eye. Why did it have to be me who discovered the fuel tank vent was clogged? I recognized the futility in dwelling on that question. Somehow, I managed to stay positive.

…

Behind schedule and less than fifteen miles south of Portland Headlight, we were treated to a beautiful sunset. The boat moved at a steady six-and-a-half knots. Life was good.

It didn’t stay that way long.

…

Brief disclaimer: The ensuing thirty-ish hours are largely a blur. My memory resembles that of a sleep deprived fever dream. At some point my brain likely decided memory consolidation was an unnecessary function. I will do my best to recollect the important details, but words cannot not do justice to what now ranks among my most trying of psychological battles to date. It was hell.

…

As night fell the wind gradually picked up. A pleasant twelve knot breeze became fifteen, then twenty-five, then thirty with added gusts. Swells grew too. Two feet morphed into four, then six, then eight, then ten, and so on. Worse yet, the sea state was confused. Hardly five seconds separated each growing peak.

The boat began to lurch aggressively without any discernible rhythm.

The horizon disappeared into a continuous blackness; I began to feel queasy. Initially, I managed by remaining in the cockpit. It was getting colder, but the wind on my face was soothing. Manning the helm provided supreme relief.

Regardless, one mistake was all it took to seal the deal. I reached into our cooler and pulled out a can of Campbell’s Spicy Jambalaya.

As I spooned soup into my mouth, I caught whiffs of the diesel which had earlier seeped deep into my gloves. Hot sausage and diesel fumes—talk about a lethal combo. Within minutes my complete focus was directed at restraining the contents of my stomach from emptying over the side of the deck.

Waves slammed into the side of the boat and over the extensive hard dodger protecting the cockpit. Our slope meter rolled from 20 degrees on one side to nearly 15 on the other. I leaned over the port-side winch and out sprayed my hardly digested dinner, twice as spicy as it tasted on the way down. I turned and faced my crewmates. “That was spicy,” I said, forcing a grin.

I felt some relief. It didn’t last long.

Shortly thereafter, on the horizon behind us, appeared a faint aura of light. We were approaching a shipping channel. No doubt these lights belonged to some type of commercial vessel. However, they were a long way off and far from a discernible threat.

“I don’t like the look of that,” Blane responded upon me pointing out the light.

“Should we try to hail them,” he continued.

Before I could respond he was hollering down the companionway, “Hey Gillramo (never once pronouncing Guillermo’s name properly), you need to come up and take a look at this.”

Blane, who was at the helm, unconsciously began to veer off course, out into the middle of the Atlantic. His agitation was rapidly transforming into hysteria.

“Can someone please tell me their course? Are we in a shipping channel? Oh my God, we are going to hit them!”

Blane was frantically steering the boat in semi-circles, the other vessel no closer to our position. I was unable to hail them on the VHF and nothing showed on our AIS. Boat traffic is not to be taken lightly, but his panic was alarmingly irrational. Prior to departing he had assured us he “got cooler under pressure.” Right. At this point, I realized it was going to be a long night.

I took the helm and assured Blane we were perfectly safe.

Conditions continued to deteriorate. The elements steadily withering away at each of us.

…

We were long overdue for a reef. For the first time, in the dark, Guillermo and I had no choice but to leave the relative safety of the cockpit. I secured my tether to a jackline and held on for dear life.

For the sake of my parents some details are better left unsaid. We completed the mission. Adrenaline coursed through my veins.

It was only after making it back into the cockpit that I realized how urgently I needed to use the head. I had been putting it off, reluctant to go below. So, down into the cabin I went, unsuccessfully bracing myself along the way.

Let me spare you the details. Suffice to say, I wasn’t the only thing getting tossed around. Every spare limb was required to keep me from slamming from one wall to another or even the ceiling. A mixture of repulsive substances sloshed about and painted my fouled weather gear with the vigorous passion of a Jackson Pollock. I covered the porcelain sink with vomit to boot.

I was miserable.

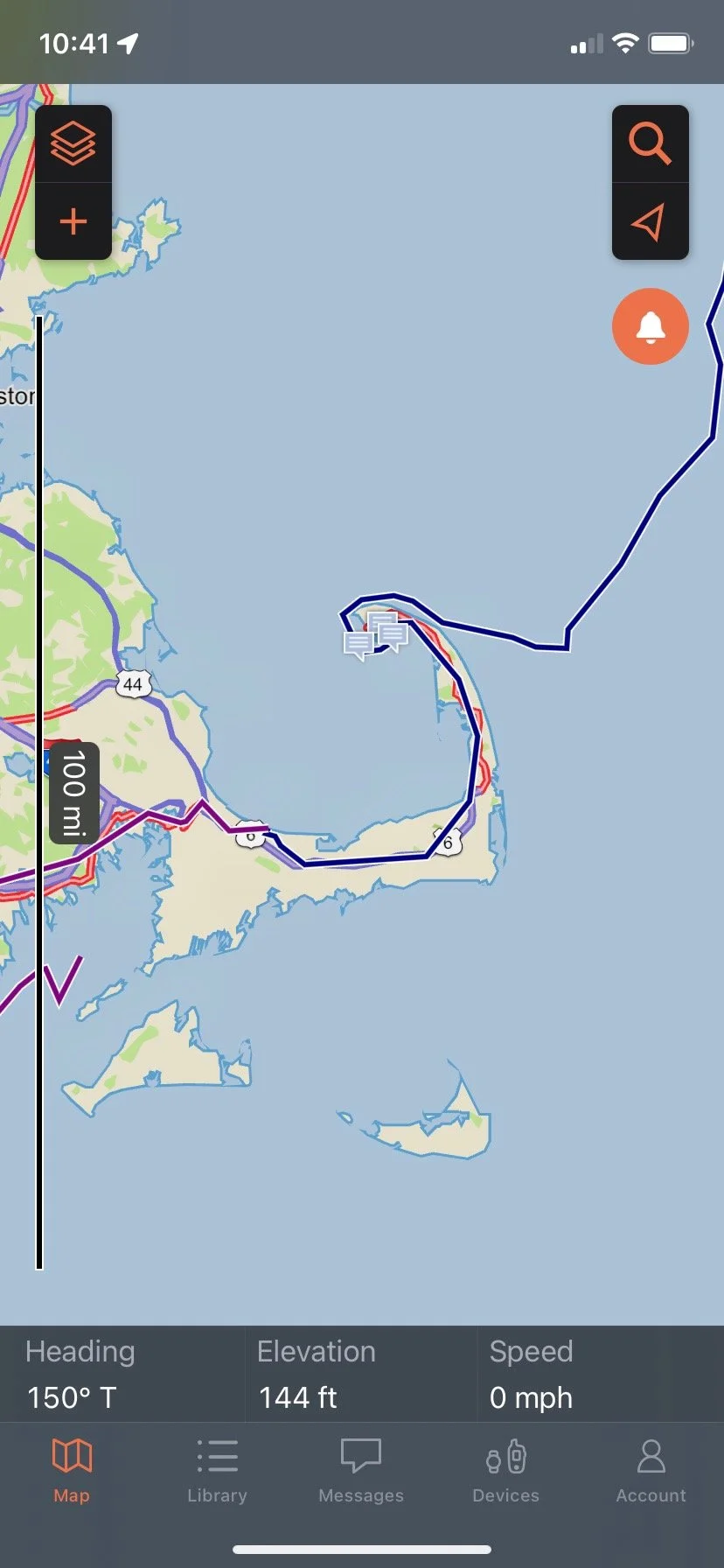

Several more tense hours passed. Blane continued to display concerning panic at every possible ship sighting. Conditions remained turbulent. We haphazardly ventured further and further offshore, eventually finding ourselves some seventy miles east of Cape Cod despite favorable winds and a plan to traverse the canal. I could not rest.

Exhausted, well past 2am, I finally went below and crashed into a berth without bothering to remove anything except my lifejacket. By then I lacked enough strength to consider changing clothes. I had thrown up and dry heaved incessantly since a second visit to the head. I was freezing and wet. What food and water I could muster into my stomach obviously didn’t stay there long. My toes and fingers were numb.

I closed my eyes. Maybe twenty minutes passed before I was called back on deck to help with a tack.

I had surpassed a reasonable level of discomfort. I was creeping beyond the boundary of what might simply be brushed off as rough shape. I knew it. I could feel my heart working hard to compensate for obvious signs of dehydration and the beginnings of hypothermia. My lower body convulsed uncontrollably. I knew much longer in the cockpit and my condition would escalate dangerously.

Again I stumbled below, this time deliriously peeling off layer after layer of wet gear. I grabbed my water bottle and tucked myself into my sleeping bag. The lee cloth hardly kept me in place but at least I felt some promise of getting warm. My body temperature rose and fell with the abruptness of a fever. Guillermo found my med kit. I weakly nibbled at two glucose tabs and took small sips of water every few minutes.

Those two hours spent curled up are probably what kept me conscious.

I hadn’t expected a gentle awakening. I also hadn’t expected to be rewarded for my much needed rest with a perilous bull ride at bow of the boat. Clearly, the latter is what I got.

Almost on queue, just after I voluntarily reemerged from the cabin, our furling line snapped. At least the sun had begun to ascend. Still, our furler dumped the genoa completely and in twenty-five knots of wind we had no option aside from pulling it down. Immediate action was made especially pressing following the discovery of water gushing in over our berths and chart table through faulty portholes whenever we exceeded twenty-five degrees of heel. A newly purchased inverter had already blown and the last thing we needed was to lose all our electronics.

I looked at Blane and said, “This is where champions are made.” Scared shitless, those words felt necessary to propel my hands into motion. I clipped myself onto the windward jackline and began forwards towards a dramatically stuffing bow. Guillermo followed along the leeward side to the mast where the halyard was tied off.

With my working tether clipped off to the bow pulpit. I began wrestling the genoa which had become hopelessly wrapped. Blane accidentally tacked the boat. I was immediately and mercilessly flogged by the sheets and sail. My stomach turned and I threw-up down the inside of my coat. Fortunately, there was not much left inside me. My eyes involuntarily widened with terror.

Guillermo signaled he was having trouble. I wasted no time getting back into the cockpit.

It was obvious I needed to be on the helm. I was sick, battered, and necessary to keep us vigilantly pointed in a constructive direction. After diagnosing the problem we initially encountered, I explained to Blane what he would need to do to guide the genoa down on a second attempt.

Guillermo and Blane headed forward. This time, though progress was slow, the genoa slowly descended. They wrangled it to the deck and tied it off. Guillermo also secured the anchor which was bobbing dangerously.

Blane redeemed himself and both managed not to die nor get seriously injured.

…

Fourteen more long hours passed before we made a final approach into Provincetown after dark. I had made an irrefutable case to seek refuge. Blane and I were hardly capable of continued service. The boat was soaked inside. More things were breaking.

Using my Garmin inReach, I desperately asked my parents to search out options on the Cape. Guillermo simultaneously studied his cruising guides and settled on a marina.

I steered all of the final six hours. Sighting land was ineffably glorious. We turned on the motor and tantalizingly inched north along the National Seashore. As we began rounding the Cape’s culminating point, a large fishing vessel began closing on us. It was clearly making a similar bearing and was leaving a healthy buffer off our starboard side. Nevertheless, Blane became mad with hysteria once more. I ignored him and stayed the course. I felt defeated.

As it passed, at least I recognized the fishing boat’s brightly illuminated stern for what it was, a God-sent beacon. I practically followed those lights to the dock.

Disregarding clear signs that the pleasure craft marina was closed for the season, we pulled along the first slip. I jumped off and secured our bowline. 8:33pm. Thirty-six hours since we cast off, to the minute.

It was over.

My aunt heroically agreed to pick me up and drive me to my grandparents’ house in Sandwich. I wasted no time packing my hundred-pound duffle. I hastily maneuvered over seagull deterrent trip lines covering every square inch of the dock. Once at the mouth of the pier, I hoisted my bag and life vest over a tall no trespassing fence, cutting every knuckle on my right hand deeply in the process. Knowing the fence wouldn’t support my weight, I balanced along a thin and unsteady wood barrier running along the perimeter and around the fence. It would have been a long and painful fall into the water.

Somehow, I made it out. I was free.

I found a bench across from George’s Pizza. Blood ran down my hand. My foul weather gear was visibly caked in a zebra print of brine. My scuba knife dangled lazily off my lifejacket and into my lap. I sat silently disheveled. An oddly eclectic nighttime crowd cast curious glances as they passed by walking down the street. A group of drunk fisherman piled out of a bar and into a pickup. A couple or two paused to take a picture in front of Cabot’s Candy. Two drag queens strolled by talking loudly.

“Hey cutie, want to make a mistake tonight?”

My response flowed out thoughtlessly.

“Thanks, but I’ve already made a few”

They liked that answer.

…

One day did a lot to get my head straight. Although it did cost my family a Thanksgiving.

For the record, my parents are too good. They drove to the Cape and helped me regroup. We cleaned my gear and loaded up on prescription seasickness medication. Many hard questions were asked.

I carefully toiled over the dangers I had recently faced. The torture was fresh in my memory. No bone in my body wanted to get back onboard. Yet, I couldn’t shake feeling that our major problems were solvable. Jumping ship without a best effort to remedy the situation felt like quitting. I could not live with that.

There is a fine line between courageous and stupid. Now, I just needed to find it.

…

On Thanksgiving Day, my dad drove me back to the boat. I would not go on without a clear and agreeable plan for the next leg.

We spent a long time discussing the tides, wind, and weather. We agreed on a short hop to boost morale, test my medication, and to get Blane ashore by Saturday. Plan A would be somewhere along the Long Island Sound. Plan B was Newport. We determined we would need to be at the canal around 11am the following day. We all voiced and talked through our concerns.

I agreed to give it another shot.

I ate Thanksgiving Dinner at a restaurant with my parents and planned to be back at the boat for a 5am departure.

…

Leg two had a contrastingly smooth start. We crossed the bay at a comfortable six-and-a-half knot pace. Seas were calm and comfortable on a close reach.

We made it to the canal a little before noon and used a slingshot current to cover the ten miles over land in less than an hour.

Sadly, that was a long as our trouble-free bliss would last. The canal opened into a menacingly choppy Buzzards Bay. Wind and waves slammed against our nose. At two-thousand RPMs we made a meager three knots.

Just before sunset we were able to crack off and get under sail. The seas mellowed and we rapidly picked up pace to seven knots. “Not so bad”, I thought.

If only you could take pictures in a gale at night!

I should have known better. Not long after dark the weather picked up. It did so at an unforgiving pace. Full blown gale conditions descended in what felt like an instant. One minute the seas had been a manageable three to five feet. The next they were an alarming ten to fifteen.

As a result, we yet again failed to reef proactively and appropriately.

Holding thirty degrees of heel, waves crashed into and over our beam. Water streamed in through our still defective portholes. I don’t know the exact size of Inga’s bilge, but at a minimum it’s many tens of gallons. Soon it was completely full, and the bilge pump was having trouble keeping up.

Propane tanks at the bow came free and were bouncing against the teak decks. Our red nav light sheared off completely. The bimini overhead seemed to hang by a thread. Howling wind shredded the Polish flag at our stern. Everything was a mess. My knuckles were ghost-white.

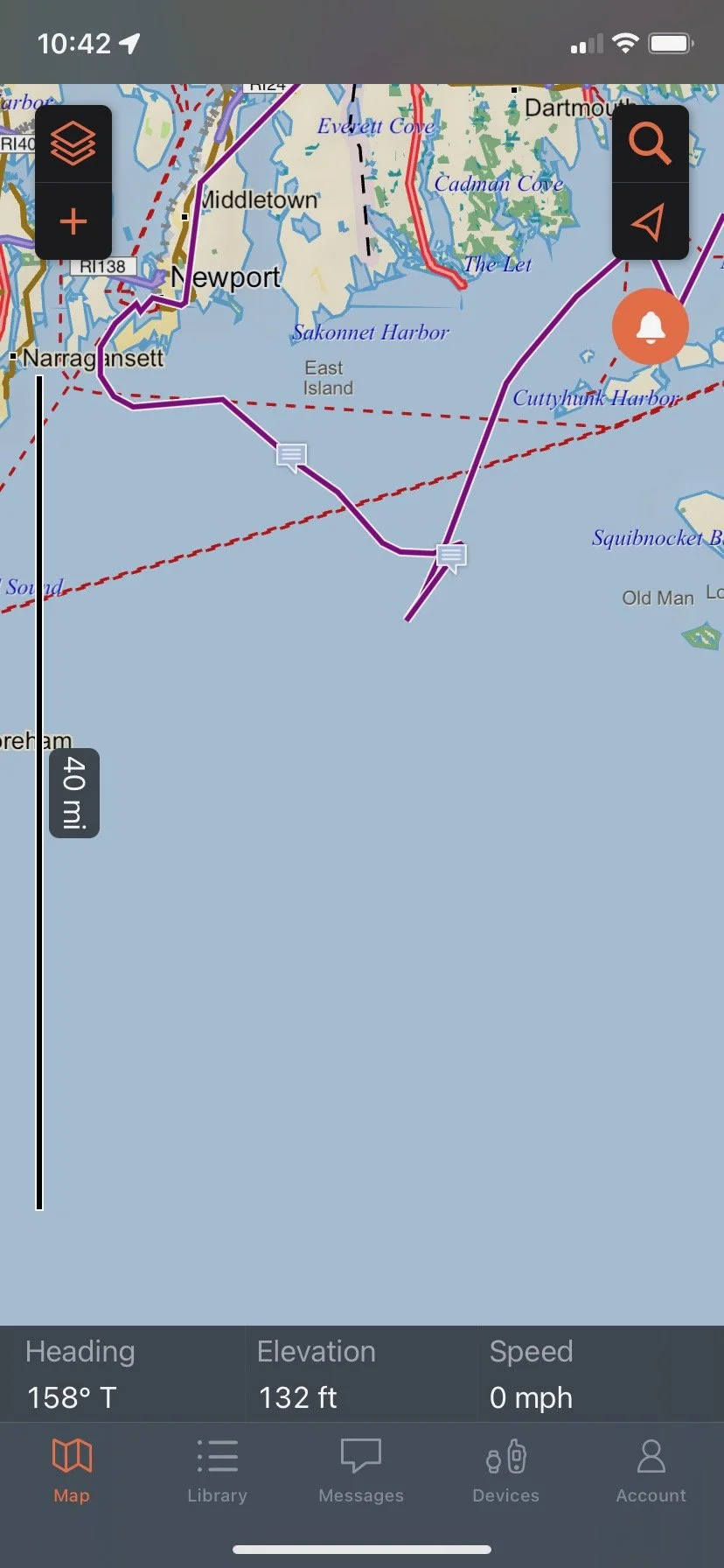

Guillermo wanted to put in a reef, but not wanting him on deck in such chaotic conditions, I instead suggested we tack and try to find some shelter back in Buzzards Bay. He agreed and we tacked back in the direction from which we had come.

The change in orientation successfully de-powered the boat. We pinched aggressively, causing us to decelerate down to one or two knots of boat speed in the large seas. Our speed wouldn’t have been so concerning except we had to recover a distance we just established while blazing along at eight knots over the past hour. Do the math! Also, at one point having lost effective steerage, the boat did a 180, causing us to gybe and one of our reef lines to get hopelessly snagged in our furling winch. Reducing sail was temporarily out of the question (Guillermo ultimately freed it with a stroke of engineering genius). My inReach started ringing. My parents had seen our course deviation. Coupled with the sudden decrease in speed, they thought I had gone overboard. Adding to our combined stress, I was not able to send anything other than a quick preset message letting them know I was still alive.

Chaos was doing all it could to destroy our tempo and concentration. We were all becoming frazzled. Despite knowing better, I nearly lost every finger on my right hand to an under-wrapped port-side winch. Crashing surf toppled into the cockpit, over us, and down every hole in my coat. On the bright-side, I wasn’t seasick!

Not making much headway we opted to drop our sails, power up the motor, and point directly for Newport. Perhaps I would have left a little main flying for stability, but Guillermo was the one out on deck doing it. I didn’t complain.

The next eight hours were spent moving tediously towards Newport. At three to four knots, it felt like eons passed between hours. The same lights onshore seemed to get closer only to teleport further away. Possibly I was just losing my mind but I began to believe we were trapped in a disturbing edition of Groundhog Day. Nonetheless, I remained steadfast on the helm until the final hour. I was unquestionably hypothermic. I have never been a fraction as cold. With only that last hour to go and in calmer conditions, Guillermo came up to relieve me. I promptly got into my sleeping bag which was draped over a soaking wet berth. I immediately passed out from exhaustion.

I awoke disoriented and inexpressibly cold through my core. Guillermo said he would need my help docking. It was 5:30am, still pitch-black aside from some festive dock lights. When I said I wasn’t sure I would be able to assist he told me the alternative would be to anchor. Needless to say, I found what I needed to get moving.

After three attempts to corral the boat in a fierce cross breeze, we were secured. Guillermo wasted no time hopping into a hot shower. I packed in less than a minute. I tossed my bag off the boat and onto dock. I jumped off and hiked to the parking lot where my concerned dad was waiting. I didn’t look back.

We dove an hour back to the Cape with Blane in tow. He was also ready to catch the first bus back to Maine.

…

I am writing this from home. At the very least, I decided to take a breather for a few days. With no weather window and many issues to address it seemed appropriate that I should take some time to process. Before completely abandoning Guillermo, I did return to Newport equipped with a long list. We had a two-hour conversation over coffee. It was surprisingly productive. We arrived at a consensus on all our shortcomings and proposed many ideas to meaningfully address them. Still, I have more than a few justifiable reservations.

I want to emphasize Guillermo did prove his exceptional sailing ability and grace under pressure. Maybe the hallmark of a master seaman is avoiding such circumstances altogether. Nevertheless, he has my respect.

…

Where does that leave my journey? I do not know. Innumerable lessons have been seared into my mind. One week has transformed me to an extent I would have previously thought to be impossibly far-fetched. A complete rewiring is taking place. Writing this post feels like a vastly incomplete snapshot—the proverbial tip of an iceberg. So many grueling details have been left out. Some very intentionally. Eventually, I hope to expand upon the more profound lessons to which this experience has made me a witness.

Beyond Newport, I may continue. I may not. It’s a decision unlike any I have faced before. The stakes and risks are infinitely more material than they appeared at the outset. I have sacrificed and invested a lot to get this far, but I also would prefer to live long enough to see things through on more acceptable terms.

Either way, more to come.